On an overcast day in the Dolomites, you can forget how high the mountains go. That is, until the clouds snag and tear on their rocky flanks, the peaks poke their heads above the smoke-white mist, and another mountain’s worth of mountain emerges on top of the mountain that already was. It would be a ridiculous, laughable height, if we had breath in our lungs for laughter. Instead it’s the mountains themselves that are amused, waving their long, stony fingers at us and craning to get a better look, chuckling at our puny striving.

On an overcast day in the Dolomites, you can forget how high the mountains go. That is, until the clouds snag and tear on their rocky flanks, the peaks poke their heads above the smoke-white mist, and another mountain’s worth of mountain emerges on top of the mountain that already was. It would be a ridiculous, laughable height, if we had breath in our lungs for laughter. Instead it’s the mountains themselves that are amused, waving their long, stony fingers at us and craning to get a better look, chuckling at our puny striving.

This could be a metaphor for aiming higher. For never underestimating anything or anyone, least of all my silly old legs, stitched and pinned or otherwise fused back together enough times it’s a wonder they have any striving left in them. We have one week in the Dolomites to hike and run as many of the peaks as we can, so long as our flesh and bones can hold themselves together.

Our first day, we stopped by the tourist office in Canazei to get a better trail map and some tips on routes. A doughy 20-something with eyelashes twice the length of the ones actually growing out of her eyelids, looked us up and down then recommended three “hikes,” all of them flat as Tyrolean Schüttelbrot, no doubt paved in sections with occasional handrails. Tyler swiftly tuned her out, flinching as her pink highlighter sullied his new map with golden-years, bunion-friendly recommendations. On what, exactly, do the young folks base their assumptions about the physical limitations of their elders? My crinkly brow and crow’s feet, presumably. My low-rise jeans. Tyler had to hustle me out of the office before I challenged her to an arm wrestle.

Our first day, we stopped by the tourist office in Canazei to get a better trail map and some tips on routes. A doughy 20-something with eyelashes twice the length of the ones actually growing out of her eyelids, looked us up and down then recommended three “hikes,” all of them flat as Tyrolean Schüttelbrot, no doubt paved in sections with occasional handrails. Tyler swiftly tuned her out, flinching as her pink highlighter sullied his new map with golden-years, bunion-friendly recommendations. On what, exactly, do the young folks base their assumptions about the physical limitations of their elders? My crinkly brow and crow’s feet, presumably. My low-rise jeans. Tyler had to hustle me out of the office before I challenged her to an arm wrestle.

For anyone, of any age, who stumbles across this blog looking to hike or run some great trails in the Dolomites and daunted by the plentitude, read on. With a six-day lift pass for the region, we made the most of the routes we could access with minimal driving throughout the Val di Fassa, running whatever we could. Often that wasn’t much: the paths were too steep, too stony, too muddy, or simply too photogenic to be rushed over so quickly. We should take lots and lots of photos so that later, when we can’t do this anymore, we have proof that we once could. That’s an actual sentence that I huffed out-loud to Tyler, who nodded and waved his phone at me so as not to waist his breath replying.

For anyone, of any age, who stumbles across this blog looking to hike or run some great trails in the Dolomites and daunted by the plentitude, read on. With a six-day lift pass for the region, we made the most of the routes we could access with minimal driving throughout the Val di Fassa, running whatever we could. Often that wasn’t much: the paths were too steep, too stony, too muddy, or simply too photogenic to be rushed over so quickly. We should take lots and lots of photos so that later, when we can’t do this anymore, we have proof that we once could. That’s an actual sentence that I huffed out-loud to Tyler, who nodded and waved his phone at me so as not to waist his breath replying.

For anyone (also of any age) wondering whether I’m going to write anything here about writing, or my book, or why I’m rattling on about aging and how these all fit together, go ahead and skip to the bottom.

Six Days in the Dolomites

Day One, with only a few hours to get our bearings, we took the gondola from Penia to the Col di Rosc, hiked the short distance to the Rifugio Fredarola, then ran along trail number 601 through the Viel dal Pan to the Lago di Fedala, catching the bus back to Penia at the end. (MAP. 6.5km, 221m elevation gain, 80% runnable.).

Day Two we took the chairlift in the opposite direction from Penia, disembarking at Ciampac and skipping the next lift and hiking the steep slope to the top of the Sela-Brunech. From here we ventured onto the Sentiero Attrezzato Lino Pederiva, which traces the backbone of the Sas de Roces. This ended up being our only ridgeline of the week, set to a soundtrack of bells tinkling closer and closer until a herd of goats and three goatherds crested over the peak in front of us and we had to step to the side so they could jingle past. At the Rifugio Passo S. Nicolo, nestled in a saddle between two peaks, we first appreciated another of the Dolomite miracles—a cozy, warm hut in the middle of nowhere and served by no roads, dishing up a hot panini and a cold radler. From here, we stumbled down trail 608 in sideways rain to Rifugio Contrin and took the (boring) 602 all the back down to Penia. (MAP. 15km, 561m elevation gain, 40% runnable).

Day Two we took the chairlift in the opposite direction from Penia, disembarking at Ciampac and skipping the next lift and hiking the steep slope to the top of the Sela-Brunech. From here we ventured onto the Sentiero Attrezzato Lino Pederiva, which traces the backbone of the Sas de Roces. This ended up being our only ridgeline of the week, set to a soundtrack of bells tinkling closer and closer until a herd of goats and three goatherds crested over the peak in front of us and we had to step to the side so they could jingle past. At the Rifugio Passo S. Nicolo, nestled in a saddle between two peaks, we first appreciated another of the Dolomite miracles—a cozy, warm hut in the middle of nowhere and served by no roads, dishing up a hot panini and a cold radler. From here, we stumbled down trail 608 in sideways rain to Rifugio Contrin and took the (boring) 602 all the back down to Penia. (MAP. 15km, 561m elevation gain, 40% runnable).

Day Three, we drove to Ciampedel and took the cable car up to the Col Rodella, started out along the 529 before branching West along the Sentiero Friedrich August to the Rifugio Sasso Piatto. Careful to avoid the branch of the 527 that continues up to the Via Ferrata Schuster, we instead descended due North along the 527, which curls around to the Rifugio Vicenza Langkofelhütte. From here, the 525 has a short runnable section, then starts to climb steeply up to the ridge between Sasso Lungo and Cinque Dita. “Stand aside,” a woman called to her friends, all of them weighed down with multi-day packs. “Young people moving fast.”

Day Three, we drove to Ciampedel and took the cable car up to the Col Rodella, started out along the 529 before branching West along the Sentiero Friedrich August to the Rifugio Sasso Piatto. Careful to avoid the branch of the 527 that continues up to the Via Ferrata Schuster, we instead descended due North along the 527, which curls around to the Rifugio Vicenza Langkofelhütte. From here, the 525 has a short runnable section, then starts to climb steeply up to the ridge between Sasso Lungo and Cinque Dita. “Stand aside,” a woman called to her friends, all of them weighed down with multi-day packs. “Young people moving fast.”

Ah, didn’t that sound good, for a moment, even if it was our sneakers and lightweight running packs, not youth, that let us power past?  And then it occurred to me that apart from a few families with young children, almost no one we’d seen tramping through these mountains was particularly young, everyone scrambling up or down the chains and rocks at his or her own pace. Most had as many decades on me as I had on the pudgy girl in the tourist bureau. And I, too, had made some assumptions.

And then it occurred to me that apart from a few families with young children, almost no one we’d seen tramping through these mountains was particularly young, everyone scrambling up or down the chains and rocks at his or her own pace. Most had as many decades on me as I had on the pudgy girl in the tourist bureau. And I, too, had made some assumptions.

We loved the climb through the mist to the saddle, rewarding ourselves with a bowl of hot minestrone and a cold beer at the Rifugio Toni Demetz at the top. Sufficiently refueled, we hopped into the tiny two-person cable car to get back down to Malga Passo. A 1km climb got us back to the top of Col Rodella and our cable-car back down to Ciampedel. (MAP. 13km, 1444m elevation gain, 35% runnable).

Day Four: this was our highest-altitude route and our closest brush with misadventure. We took the big cable car from Penia, ran the 2km to Pas Pordoi and took a second cable car up to Sas Pordoi. This mountain sticks up like a molar above the other peaks and, for us, was dusted with fresh snow. We mostly ran the 627 to Rifugio Boè, at the base of Piz Boè, then continued along the 647 past L’Antersas, avoiding the Via Ferrata Koburgerweg on 647A. At the junction of the 647 and the 649, we branched right, then soon after took the 666 to Rifugio Cavazza Al Pisciadu, descending via a hair-raising series of chains and spikes bolted into the rock to the glacial lake Pisciadu, all exhilarating, all raw, all beautiful.

Day Four: this was our highest-altitude route and our closest brush with misadventure. We took the big cable car from Penia, ran the 2km to Pas Pordoi and took a second cable car up to Sas Pordoi. This mountain sticks up like a molar above the other peaks and, for us, was dusted with fresh snow. We mostly ran the 627 to Rifugio Boè, at the base of Piz Boè, then continued along the 647 past L’Antersas, avoiding the Via Ferrata Koburgerweg on 647A. At the junction of the 647 and the 649, we branched right, then soon after took the 666 to Rifugio Cavazza Al Pisciadu, descending via a hair-raising series of chains and spikes bolted into the rock to the glacial lake Pisciadu, all exhilarating, all raw, all beautiful.

From Pisciadu, route 677 betrayed us. Dotted across a slope of boulders, the trail markers were few and far between, painted on tumbled stones that seemed to have been partially swept down the hill, the red and white swatches eventually petering away to nothing.  We were hoping to connect with the 649 to return to the 647, but the only thing resembling a plausible route was a steep, wet gash in the mountainside with no reassuring signage, the few iron cables and signposts crumpled like tin. Clambering higher over the loose rocks, we could hear running water and felt the glacier beneath us creak and groan, everything inching nervously downhill. With just three hours before the last cable car of the day back at Sas Pordoi, we made the (wise) choice to hoof it back 13km the way we’d come, past Pisciadu, up the chains, and over the snow-brushed ridges, retracing our steps in half the time. Only when we were safely back in Canazei did our fantastic adventure seem just that, and we vowed we’d do our best not to repeat it. The better route for Piz Boè might be to return from Rifugio Cavazza Al Pisciadu along the 676 and the 651, but we didn’t try that. (MAP. 27km, 2700m elevation gain, 25-50% runnable, depending on how desperate you are not to spend the night on top of a mountain).

We were hoping to connect with the 649 to return to the 647, but the only thing resembling a plausible route was a steep, wet gash in the mountainside with no reassuring signage, the few iron cables and signposts crumpled like tin. Clambering higher over the loose rocks, we could hear running water and felt the glacier beneath us creak and groan, everything inching nervously downhill. With just three hours before the last cable car of the day back at Sas Pordoi, we made the (wise) choice to hoof it back 13km the way we’d come, past Pisciadu, up the chains, and over the snow-brushed ridges, retracing our steps in half the time. Only when we were safely back in Canazei did our fantastic adventure seem just that, and we vowed we’d do our best not to repeat it. The better route for Piz Boè might be to return from Rifugio Cavazza Al Pisciadu along the 676 and the 651, but we didn’t try that. (MAP. 27km, 2700m elevation gain, 25-50% runnable, depending on how desperate you are not to spend the night on top of a mountain).

Day Five was our hands-down favourite. It began with the gondola from Vigo di Fassa to Ciampedie. From here we ran and hiked the Alta Via dei Fassani to Malga Vael, scrambled up the short steep climb to Rifugio Roda di Vael, then had a gorgeous, 5 KM run around the mountain on 549 to Rifugio Fronza/Köülner Hütte. From here (after beers and fried potatoes), we scaled route 550 up through the spectacular Pas de le Coron ele, then plunged down the 550 on the other side before taking the 541, most of it runnable, until the intersection with the black, unnumbered trail that led us back around the mountain. At the junction with another black trail at Pale Rabiouse we kept left to drop all the way back to Campedie. The steeper sections on this route were relatively short and spectacular, and the rest of the trail mostly smooth and flowy, with craft beer at the top of the cable car before our return to Vigo di Fassa. (MAP. 17km, 1200 elevation, 70% runnable).

ele, then plunged down the 550 on the other side before taking the 541, most of it runnable, until the intersection with the black, unnumbered trail that led us back around the mountain. At the junction with another black trail at Pale Rabiouse we kept left to drop all the way back to Campedie. The steeper sections on this route were relatively short and spectacular, and the rest of the trail mostly smooth and flowy, with craft beer at the top of the cable car before our return to Vigo di Fassa. (MAP. 17km, 1200 elevation, 70% runnable).

Day Six came too soon; we elected to keep it short and steep. Parking at the Rifugio Capanna Cima Undici overlooking the Lago di Fedala, we hiked the 618 until branching left on the 619, then continuing up to the base of the glacier along trail 909. After the requisite beer and apfelstrudel at the Rifugio Pian dei Fiacconi we took the creaking, rather terrifying, open air, “two breadsticks in a breadbasket” lift back down to the car. (MAP. 5km, 675m elevation, 1% runnable).

(Anyone wise enough to try to emulate our Dolomites adventure might also want a hotel tip: while there are plenty of hotels in the region, we stayed at Chalet Vites, which was absolutely gorgeous with a scrumptious breakfast, plus a (free) spa complete with sauna and steam-rooms to help ease our aches and pains.)

*****

Dolomite, the rock, is 230 million years old, made of coral and other sediments from the bottom of a sea long gone. A mere 65 million years ago, the rock was thrust high into the air by shifting tectonic plates creating this jagged range which stretches across Northern Italy from the River Adige in the west to the Pieve di Cadore in the east. Today the mountain tops are an ashen mix of calcite and magnesium curved in places like a set of chipped, stained teeth, sharpened into points. The meadows and trees at their roots form plush, green gums, receding towards the valley bottom.

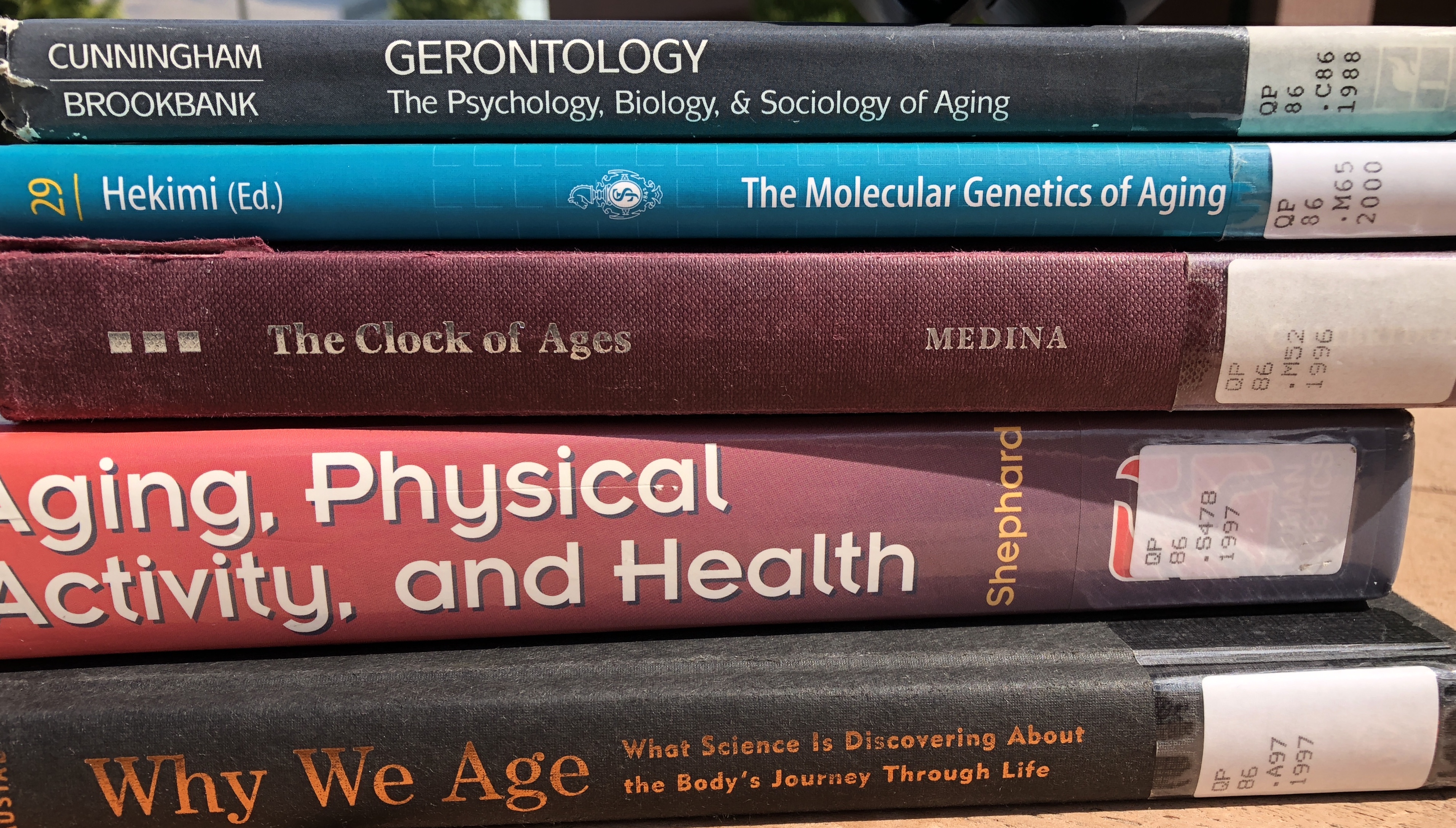

Oh, another metaphor of aging. It’s much on my mind: not merely the injuries that outstay their welcome or the surprising, faintly comforting way the skin on my arms has started to remind me of my mother. The thing is, I’ve an idea for my next novel and for this I’m researching aging. I’ve been signing out books from the library and calling up geneticists and biochemists, trying to get a better grasp on growing old, at a cellular level. Last month I borrowed half a shelf of books on gerontology and aging from the UBC library. Walking back to my car, feeling middle-aged among the scurrying students, I had a vivid image of myself and the stack of desperate titles in my arms, slumping across campus in unfashionable shoes. I had to set the books down: that’s how hard I was laughing.

Oh, another metaphor of aging. It’s much on my mind: not merely the injuries that outstay their welcome or the surprising, faintly comforting way the skin on my arms has started to remind me of my mother. The thing is, I’ve an idea for my next novel and for this I’m researching aging. I’ve been signing out books from the library and calling up geneticists and biochemists, trying to get a better grasp on growing old, at a cellular level. Last month I borrowed half a shelf of books on gerontology and aging from the UBC library. Walking back to my car, feeling middle-aged among the scurrying students, I had a vivid image of myself and the stack of desperate titles in my arms, slumping across campus in unfashionable shoes. I had to set the books down: that’s how hard I was laughing.

This is all terrifying: the actual aging—loving what my body can do and dreading the day it can’t—but also this book, insisting itself upon me. I’m scared I won’t find the hours or discipline to slot another writing project into a life so crammed already with work and laundry, friends and groceries, love and mountains. Time’s waistband is only so elastic. To draft my first novel, I quit my job of 14 years. To polish the final chapters, I developed a seemingly imaginary stress fracture in my foot that put a stop to running and cycling; I turned down invitations to do fun things with friends. What if life doesn’t allow the space and time for another book to be born and come of age?

I have to squeeze it in, that’s how it feels. This book has been chiming with my innermost bells, inserting itself in my sleepless, jetlagged nights. Characters I’ve never met are pushing their unruly hair from their eyes in crowded lecture halls and learning sleight-of-hand on the deck of a rolling ship. Yes, I’m confessing this here in the hopes that setting it down will make me more likely to get it done. I don’t remember the first book feeling this way, tugging at my sleeve and mumbling. If it did, I’ve forgotten.  This happens, I gather, as you age.

This happens, I gather, as you age.

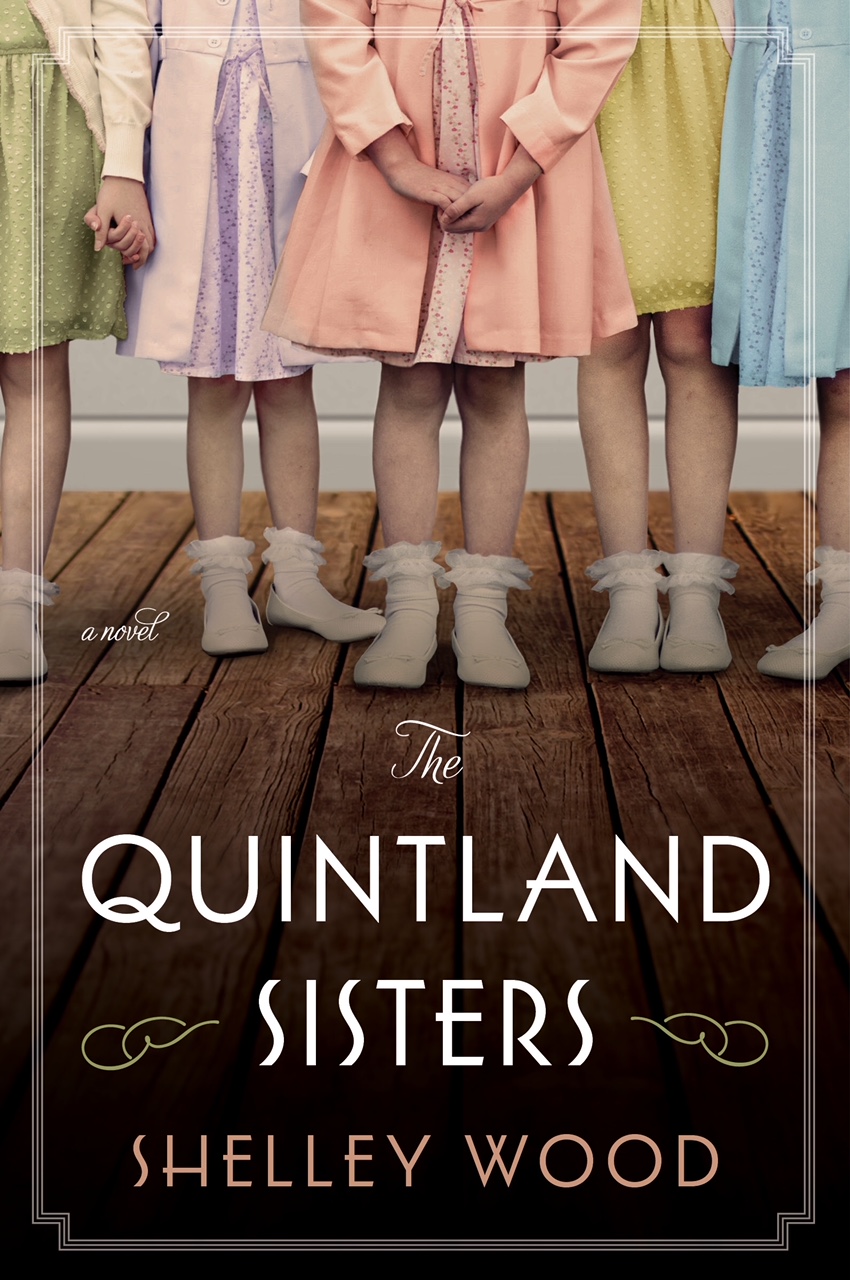

The first book—it’s coming. The Quintland Sisters will be out March 5, 2019, and you can already order it online in the United States and Canada. In fact, I have others news, even more surreal: just last month I officially signed over worldwide English language rights to HarperCollins 360. This means, I gather, that The Quintland Sisters will also be available in India, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, the UK, and who knows where else sometime next year. This is the candy I’m sucking at the back of my mouth when all other things seem too hard. This is the skip in my step, when everything might otherwise feel too exhausting, too steep, too broken-down and aching, too old before its time.

Big thanks to Rene Unser for recommending the Dolomites in the first place.