The jolt and hum of the train, the green hills smudging past and, across the aisle, my nieces—two coltish girls on the thorny cusp of womanhood. They are twirling their fingers in their ponytails, cramming baguette into their mouths and, unexpectedly, setting aside their cell phones to read the novels I’d sprung on them before we boarded.

The jolt and hum of the train, the green hills smudging past and, across the aisle, my nieces—two coltish girls on the thorny cusp of womanhood. They are twirling their fingers in their ponytails, cramming baguette into their mouths and, unexpectedly, setting aside their cell phones to read the novels I’d sprung on them before we boarded.

We’ve survived a week in France together: me, Tyler and, it seems, the children we’d long ago elected not to have ourselves.

“I thought your daughters were twins,” one woman cooed at us in the airport.

“Is your daughter finished?” the flight attendant asked before reaching across to take Sophie’s tray.

It’s too complicated to correct the public assumptions. Later, when Maddy’s luggage goes missing for days and I have to harangue British Airways, in French, it seems easier to demand how they expect my daughter to go without clean clothes for 72 hours in Paris.

I’d been anxious about this trip—a long-promised vacation in lieu of a decade’s worth of Christmas gifts and birthday presents. I worried the girls would be bored or homesick, worried we’d lose them to crowds or Russian pimps. Worse, maybe: I worried we’d max out on them long before the week was up or that they would grow weary of our bungled parenting and act up, act out.

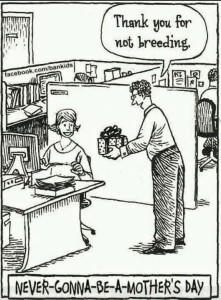

And day two of our vacation was Mother’s Day, a miserable milestone, I’m sure, for anyone who ever wanted children and couldn’t or didn’t. For me it’s just another calendar reminder of the mother I’ve lost, who I miss with a force that can still step sideways out of a sunny moment and swing a bat at my chest. The best thing to do is pretend it’s just a day like any other, only worse, best spent avoiding florists, brunch, and social media.

Or, apparently, a day to trek out to Versailles with someone else’s children. We wake the girls at dawn, urge comfortable shoes and a sweater for the long lines, then shepherd them to the early train. In a vulnerable moment, I make the mistake of thinking of my mum and our travels, of Mother’s Days past, and the tears bubble up. The girls cast me anxious glances, but I brush their worries aside, make light of it. Oh, I feel things deeply, I explain. Beauty and sandwiches are enough to set me off.

This is the aunt I’ve always hoped I could be. Not a substitute mother but an alternate model of grown-up woman: no more or less fulfilled, simply busy with my own big life. Ushering them around Paris and Versailles, then across the Dordogne—by bike, no less— I surprise myself by succeeding, as best as I can tell. Who knows what they’re texting their parents or what flawed and fleeting record Snapchat makes of our little excursion, but everything feels easy and heartfelt. Their hugs come at us like a mugging. The mood on our final day, in the cozy whoosh of the fast train back to Paris, feels family-ish. After we delivered them safely back to their dad, I assumed I’d feel a sense of duty discharged. Instead, I catch myself thinking: I would do this again.

It strikes me that, content as I am to give them back, this is also the first true glimpse I’ve had of the road not taken—the fierce protective instinct that surged when a truck passed too close to their bikes, the swell of love and pride that catches me off-guard at the sight of them absorbed by their books or pedaling earnestly up a hill, elbows jutting. It occurs to me that my own mother, who accepted but scarcely understood me never giving her grandchildren, would be proud of me, too.

HT: L. Volk for the cartoon.