I am a very occasional poet. The urge, the wisp of an idea for a poem, wafts by once every three years and it’s hit or miss whether I bother to write it down. And yet I love poems, love the hard, tight punch of them, how they can crack you wide open with a single line. I love words, so I love the way poetry can make them clang together and still sing. Poems also confound me. I can sense when they are perfect, when the lines have come together faultlessly, but I rarely understand how to get them there. Sort of like a Rubik’s cube.

I am a very occasional poet. The urge, the wisp of an idea for a poem, wafts by once every three years and it’s hit or miss whether I bother to write it down. And yet I love poems, love the hard, tight punch of them, how they can crack you wide open with a single line. I love words, so I love the way poetry can make them clang together and still sing. Poems also confound me. I can sense when they are perfect, when the lines have come together faultlessly, but I rarely understand how to get them there. Sort of like a Rubik’s cube.

I never solved the Rubik’s cube as a child, although I often contented myself with making pretty patterns on one face and seeing if I could replicate that on another. It got me thinking, if you took a poem and mixed up the words, would you still have poetry? Not the same poem, of course, but something equally provoking?

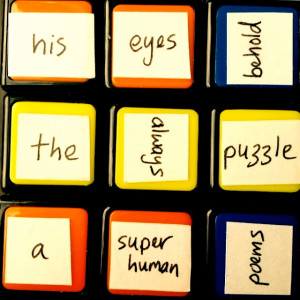

So, for my writing class, I wrote a Rubik’s poem.

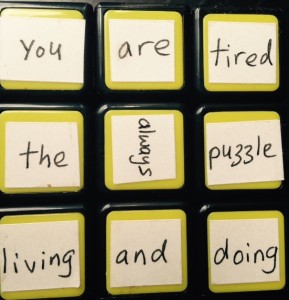

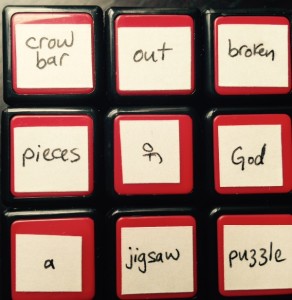

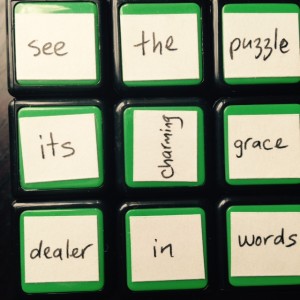

First I  hunted for poems by established poets that contained the word “puzzle” then I pulled words and phrases from the poems to write six couplets containing nine words each. The source poems were: “Rain Towards Morning” by Elizabeth Bishop; “you are tired” by e. e. cummings; “Bride and Groom Lie Hidden for Three Days” by Ted Hughes; “The Civil War” by Anne Sexton; “Sword Blades and Poppy Seed” by Amy Lowell; and “To Foreign Lands” by Walt Whitman.

hunted for poems by established poets that contained the word “puzzle” then I pulled words and phrases from the poems to write six couplets containing nine words each. The source poems were: “Rain Towards Morning” by Elizabeth Bishop; “you are tired” by e. e. cummings; “Bride and Groom Lie Hidden for Three Days” by Ted Hughes; “The Civil War” by Anne Sexton; “Sword Blades and Poppy Seed” by Amy Lowell; and “To Foreign Lands” by Walt Whitman.

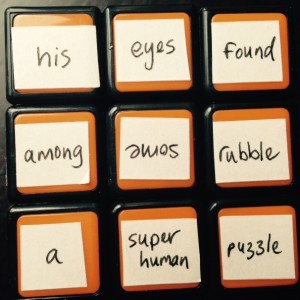

I put each of my found puzzle poems on a Rubik’s cube I bought for 11 bucks at Toys ‘R Us. (There may be no other way to find poetry at a Toys ‘R Us). Out of its rigid plastic packaging, the Rubik’s cube comes solved, so each couplet was transferred to a completed face of the cube, one on red, one on blue, etc. Then I told my class about my Rubik’s poem and it got passed around the room.

“May I?” said the first person. I nodded, pleased with myself, and he swiveled some faces and made a new poem. So did the next and the next. I could feel the first prickles of perspiration. How hard will it be to solve my Rubik’s poem again? I watched the coloured squares twist and turn. I took a deep breath. I’m a grown-up now, I reminded myself. I can crack this sucker.

“May I?” said the first person. I nodded, pleased with myself, and he swiveled some faces and made a new poem. So did the next and the next. I could feel the first prickles of perspiration. How hard will it be to solve my Rubik’s poem again? I watched the coloured squares twist and turn. I took a deep breath. I’m a grown-up now, I reminded myself. I can crack this sucker.

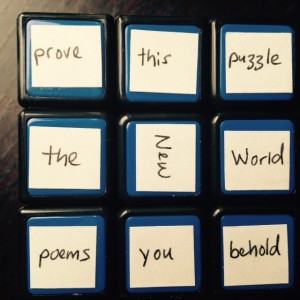

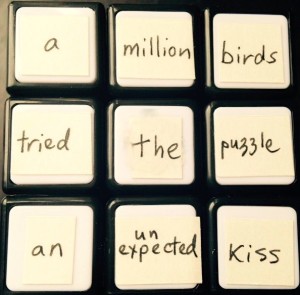

By the time I got it back, the new poems were a mix of gibberish and awesome.

a million birds

solved the puzzle

so unexpectedly simple

Over the next 24 hours I puttered with the cube and made zero headway. Then I had to pack my bag for France. I’m taking French classes in Paris, plus hoping to write and eat good things, walking as much as possible so that both of those things don’t end badly for me.

“You’re taking that?” Tyler said, when he saw the Rubik’s poem going into my hand luggage. I’d already announced that I’d nixed a pair of dress shoes and a proper coat from my checked bag. Now my husband was blanching at the image of me, ensconced at an outdoor table at Les Deux Magots in my sneakers and green Gortex jacket, trying to solve my Rubik’s poem.

“You’re taking that?” Tyler said, when he saw the Rubik’s poem going into my hand luggage. I’d already announced that I’d nixed a pair of dress shoes and a proper coat from my checked bag. Now my husband was blanching at the image of me, ensconced at an outdoor table at Les Deux Magots in my sneakers and green Gortex jacket, trying to solve my Rubik’s poem.

“With this,” I said, and showed him the six-page “Solve the Rubik’s Cube” manual I’d printed off the internet.

I pulled the cube out on the flight from Kelowna to Vancouver.

“I haven’t seen one of those in ages,” the flight attendant said. Tyler, next to me, tried to sink a bit deeper into his seat. “With words!” she exclaimed. “That looks hard.”

“They’re poems,” I said, hoping to enhance Tyler’s mortification. “But I’m actually just trying to solve the colours.”

“I would find the words distracting,” she said.

This is always true.

“You’re not exactly solving it yourself if you’re using the instruction booklet,” Tyler murmured. I was trying to hold the instructions as unobtrusively as possible, pinning them to my lap with my elbows while I glowered at the cube and tried to look intelligent.

“You’re not exactly solving it yourself if you’re using the instruction booklet,” Tyler murmured. I was trying to hold the instructions as unobtrusively as possible, pinning them to my lap with my elbows while I glowered at the cube and tried to look intelligent.

“Actually it is,” I told him. It hadn’t occurred to me (here’s a clue as to why I’d never solved the cube as a child) that printing off the solution manual in black and white would be of scant help for a puzzle based on six different colours. “So it’s still extremely challenging,” I explained.

“I used to be able to do that thing in two minutes,” he said, then went back to pretending we weren’t travelling together.

By the tim e we’d crossed the Atlantic I’d only completed the white face (easy-peasy) and matched the upper edges to the center pieces before falling asleep.

e we’d crossed the Atlantic I’d only completed the white face (easy-peasy) and matched the upper edges to the center pieces before falling asleep.

“You’re doing that here?” Tyler said when the Rubik’s poem came out again at Heathrow. His tone implied that I’d started waxing my legs at our boarding gate.

“I’m solving the middle layer,” I told him crossly. Jetlag is no help for puzzles or poetry.

On our last hop from London to Paris, I solved my Rubik’s poem. I wanted to share the moment with someone, but I already loathed the man beside me because he’d refused to swap seats with Tyler, who was four rows behind. If the man had tried to make conversation with me by asking about my Rubik’s poem I was going to shake my head and act like I didn’t spe ak English. I held the completed cube up in the air and waved it around, trying to get a laugh or applause out of Tyler, but when I turned around to look, he had his eye mask on and was sleeping, or more likely, feigning sleep.

ak English. I held the completed cube up in the air and waved it around, trying to get a laugh or applause out of Tyler, but when I turned around to look, he had his eye mask on and was sleeping, or more likely, feigning sleep.

The strange thing is, while I’ve got my poems back, they are not completely perfect. In some cases, my center squares are sideways, which I find comforting. As if, even when you get a poem perfectly right, there is always room for surprises.

FWIW: I was taking a course requiring me to write a weekly-ish blog, sometimes about the works we’d read in class or the stuff we were writing, or sometimes about new encounters or experiences, particularly those that involve other art forms. This is the last of the batch. Other class blogs are here, here, here, here, here, and here. If these posts seem different from those in the past, this is why.