At 3:15 the steep, snow-crusted slope at the end of the sports field started bowling out teenagers like they were cans of pop rolling out of a Coke machine. I was waiting for my almost thirteen-year-old niece on the street behind her high school to avoid the traffic jam in front. Big and small teenagers, slouched and pimply teenagers, under-dressed teenagers: all of them had slim, white wires curling out of their ears and into their pockets — the essential, extracorporeal vasculature of the not-yet adults.

At 3:15 the steep, snow-crusted slope at the end of the sports field started bowling out teenagers like they were cans of pop rolling out of a Coke machine. I was waiting for my almost thirteen-year-old niece on the street behind her high school to avoid the traffic jam in front. Big and small teenagers, slouched and pimply teenagers, under-dressed teenagers: all of them had slim, white wires curling out of their ears and into their pockets — the essential, extracorporeal vasculature of the not-yet adults.

“So what are we going to do?” I asked my niece when she got into the car, jacketless, hunched with cold. I’d thrown out some options earlier: walk the dog, go skating, go swimming, bake cookies.

“I don’t know.” She wriggled her shoulders. “Whatever you want.”

I dragged her to the art gallery.

I haven’t been to the art gallery in years and know less about the visual arts than I think I should. So it wasn’t that I thought I could teach my niece anything about art, it was that I hoped I could instill in her something about aesthetics, or even more simply, likes and dislikes. Opinions. She’s almost thirteen, for god’s sake. What a precipice.

I parked the car. “We’re going to play the art game,” I said in my most animated voice. I couldn’t imagine how to give this outing even a whiff of fun without turning it into a game. “To play the art game, you say the word ‘This!‘ and you do this”— here I made a dramatic arc-and-point gesture, like I was indicting Professor Plum with the lead pipe in the library— “and you point at a work of art.”

My niece gave a small and indulgent smile. She’s been induced to play my so-called games in the past.

“Then I, in response, need to oblige you by telling you whether I like that particular piece of art and why. The why is the important part. It doesn’t matter whether you like it or not, or whether you think I like it or not. You just need to have your own opinion and a reason.”

My niece nodded and we went into the gallery.

I worry about this niece, my eldest niece. I worry she is so eager to please she’s lost her way back to her own point of view. I want her to be able to judge good and bad for herself regardless of what other people think. I worry this might be true for most nearly-teenage girls, but I also know I worry too much.

“I actually know very little about art,” I confess. “But I know that it’s like music or movies or books, and even people. Especially people. You can like or dislike whatever or whomever you want, but make sure you are clear with yourself about it and see if you can tell yourself why.”

My niece just nodded. Kooky Aunty Shelley.

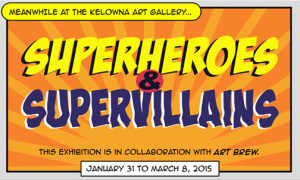

W e enter the Superheroes & Supervillains exhibit.

e enter the Superheroes & Supervillains exhibit.

“This!” I say, and do my exaggerated sweep-and-point in front of what appears to be an acrylic of space-travelling farm animals.

“I like it,” she says.

“Why?”

Shrug. “It’s funny.”

“Okay, your turn.”

She gamely does a wide swing of her skinny arm and points at a painting of a chubby unicorn with pink hooves. “This!”

Damn. I’m stumped. I don’t feel strongly about this either way. It looks to me like something the talented kids in my grade seven class would have painted back when I was in thirteen. It also looks vaguely familiar.

“Gee, I don’t know,” I admit. “You got me. I guess I like it, but it doesn’t move me. It doesn’t seem original.”

“It’s from Despicable Me!” my niece informs me. “It’s Agnes’s unicorn.”

Huh.

“So you like it?” I ask her.

“Ya. It’s cute.”

I drag her to another section of the art gallery. This is the feature exhibit, A Terrible Beauty: Edward Burtynsky in Dialogue with Emily Carr.

Here we are both struck by Burtynsky’s photos, their colour and scope, the environmental transformations and devastations they capture, made beautiful through his compositions. I had thought it would be a treat to see the Emily Carr paintings that Burtynsky’s images are paired with, but ultimately it is the photos that grab us, both me and my niece. “This.” I say to her and we study an aerial shot of a hillside, heavily terraced by agriculture. Humans hewing a life out of every inch of land they have.

“That’s my favourite,” she surprises me by saying. “I like the shapes and the greens.”

We leave the gallery and set off down the street for hot chocolate with whip cream. It’s a foregone conclusion that the chocolate and cookie denouement of the afternoon will win out as the enduring high point of this outing when it gets recounted to parents and grandparents. That’s okay.

Outside the Rotary Centre for the Arts, I pause. “Let’s just pop in here quickly and see if we can see any artists actually working.”

My n iece, no doubt weak with hunger and cold to the bone, quietly acquiesces. We peer briefly at a dance class, then wander down a hall cluttered with paintings and sculptures. Through an open door: bingo. Crystal Przybille, an acquaintance of mine and renowned sculptor, is glowering at a clay figure on the table in front of her. We invite ourselves in and Crystal kindly walks us through what she’s doing. This piece has been commissioned by the Westbank First Nation and will eventually be a life-sized bronze sculpture of Chief Sookinchute. For now, she’s trying to perfect the miniature version, in brown clay, that will then need to be waxed and cast and tweaked and enlarged. I can scarcely follow all the steps of the process myself, so I know my niece has likely lost the plot. Crystal explains that she did extensive research into Sookinchute’s late 19th century apparel and headdress—she gestures to photographs on the wall—then actually crafted the headpiece as best she could with animal hide, fur, and feathers. And here it is, the headdress, sitting in front of her on her 21st century workbench.

iece, no doubt weak with hunger and cold to the bone, quietly acquiesces. We peer briefly at a dance class, then wander down a hall cluttered with paintings and sculptures. Through an open door: bingo. Crystal Przybille, an acquaintance of mine and renowned sculptor, is glowering at a clay figure on the table in front of her. We invite ourselves in and Crystal kindly walks us through what she’s doing. This piece has been commissioned by the Westbank First Nation and will eventually be a life-sized bronze sculpture of Chief Sookinchute. For now, she’s trying to perfect the miniature version, in brown clay, that will then need to be waxed and cast and tweaked and enlarged. I can scarcely follow all the steps of the process myself, so I know my niece has likely lost the plot. Crystal explains that she did extensive research into Sookinchute’s late 19th century apparel and headdress—she gestures to photographs on the wall—then actually crafted the headpiece as best she could with animal hide, fur, and feathers. And here it is, the headdress, sitting in front of her on her 21st century workbench.

“That’s amazing,” I say, gazing from the photos, to the furred and feathered hat, to the little clay figure on the table. I want my niece to realize that this is pretty amazing, but her eyes are bouncing around the room in search of something more interesting, or perhaps edible.

“Now I’m trying to recreate it out of clay,” Crystal says, sounding exasperated. She laughs. “Feathers out of clay. It’s hard.”

I take my niece, at last, to the cozy café where we eat and drink sweet things that will partly spoil our dinner. I try to loop back to the life lessons I’d been attempting to impart at the gallery, but in the end decide our time is better spent with me just listening to what an almost thirteen-year-old might feel like telling me. She shows me some photographs on her smartphone that she took for her photography class and I’m impressed by her eye and by how she approached her subject matter. Phew. Someone else has her visual arts education in hand.

Later it occurs to me that I learned something about art and the small and daunting steps that need to be taken before anyone can say, that’s it, I’m done. I’d accidentally dragged my niece into a lesson I myself needed about hard work, taking the long-view, and leaps of faith. I think I can apply this to my writing if not to my nieces (although, poor ducks, I’m unlikely to stop trying). So I’ll keep chipping away day by day on my own project trying to keep a clear sense of its final shape in my head, along with my fragile belief that the work will likely pay off. And I’ll stick to the assumption that a day will come when I can say: Ah, this. This I like. Here’s why.

Later it occurs to me that I learned something about art and the small and daunting steps that need to be taken before anyone can say, that’s it, I’m done. I’d accidentally dragged my niece into a lesson I myself needed about hard work, taking the long-view, and leaps of faith. I think I can apply this to my writing if not to my nieces (although, poor ducks, I’m unlikely to stop trying). So I’ll keep chipping away day by day on my own project trying to keep a clear sense of its final shape in my head, along with my fragile belief that the work will likely pay off. And I’ll stick to the assumption that a day will come when I can say: Ah, this. This I like. Here’s why.

FWIW: I’m back at school, taking a course requiring me to write a weekly-ish blog, sometimes about the works we’re reading in class, sometimes about new encounters or experiences, particularly those that involve other art forms. If these posts seem different from those in the past, this is why.