“No matter what,” my husband says, “we need to get my mother on an elephant before we leave India or this whole trip is a bust.”

“No matter what,” my husband says, “we need to get my mother on an elephant before we leave India or this whole trip is a bust.”

I agree. Pat will love an elephant ride. It will be a highlight of the holiday. It’s only on the long dusty drive from Agra to Jaipur that I read my personalized itinerary closely and realize that all four of us are scheduled to travel by elephant up to the Amber Palace.

Good lord, I think, mind already scrambling for excuses. I don’t need to ride an elephant. I love elephants too much to subject one to the indignity of ferrying me up to an ancient palace. I’m tired of sitting so much anyhow. I’ll run up; I’ll carry the elephant treats.

I’ve spent years budget backpacking or at least making my own way through foreign lands; this is my first truly scripted vacation. Personalized itineraries; hotels booked; a gleaming white van and driver who could have excelled as a Hollywood stuntman; a succession of guides and chaperones ushering us to the front of the queues at India’s must astonishing sites, supplying us with water before we even know we’re thirsty. We’re paying top dollar, but it’s been an absolutely effortless way to show this extraordinary country to Tyler’s parents. Their jaws have yet to snap back into resting position since we touched down in Delhi.

Our guide through Rajasthan is Subir. He is a short, middle-aged man with a spiky mustache and a limp. He needs a knee replacement but is putting it off as long as possible, solemnly informing me that one’s own, man-made body parts, no matter how broken down, are better than imported body parts. Subir is the master of the one-liner and will deliver these poker-faced, eyelids at half mast, his gaze flickering from side to side, trying to leash in his own laughter until you get the joke.

“Did I tell you what happened a few years ago with the elephants?” he asks me. This in response to my query as to whether elephants were the only means of attaining the Amber Palace. “No,” he checks himself. “I will tell you after the elephant ride. But you will enjoy it, truly. You must ride an elephant once in your life. Me, I am taking a jeep.”

“Do you think your mum ever rode an elephant?” my husband asks. Another thing I don’t know and can’t ask her now. I have the sense he does this to let me know he knows she’s on my mind, and to include her on this adventure with his parents. Also, perhaps, to remind me that the chance to ride an elephant may never come again. I know mum rode a camel in Morocco. She and my dad travelled to India before I was born but I have no idea if they went to Rajasthan.

Before we came to India, we talked endlessly about what we should wear. When I was here 15 years ago, I had precisely two outfits. One faded T-shirt paired with a long, blue skirt that I learned after months on the subcontinent had the cut and style of a petticoat that should be worn, unseen, under a sari. My other outfit was a salwar kameez bought in Chennai shortly after I arrived. Billowing tunic and poofy pants — I wore it most days, washing it in my sink at night. It would always be dry by morning.

But India is more Westernized now, I reasoned, and I’ve outgrown the solo bohemian image I was striving for in my 20’s. What I needed were some linen slacks and flowing shirts. I wouldn’t blend in with the locals (had I ever?) but I’d be an understudy for that familiar cast of beige, unremarkable characters the world over: the older lady traveller.

After mum died, I kept every item of clothing I could ever imagine wearing, and a few things of hers I couldn’t face never seeing again. The rest got bundled into a dozen green garbage bags last September and left in her living room for my brother to take to a charity. When I went back to Vancouver at Christmas, the bags were still there, propped against one another in her cold home, supporting one another in their grief.

By then I’d remembered her rough cotton capri pants and white linen blouses, cut long and loose and jumbled into those bags. It took some digging but I found them. Now, months later I’m wearing them around India, pleased that a piece of my mum is making this journey with us after all.

The problem with wearing bland and shapeless clothes in India (with your sneakers, because you have high arches and never know when you might be able to go for a run ) is that you always feel ugly and ungainly. This is in contrast to all the beautiful women around you, swathed in saris and kameezes in the brightest colours and glossy silk embroidery. They wear bangles on their arms and rings on their toes. Me, I’ve left any jewelry, make-up, even my hairdryer in Canada; I haven’t felt so frumpy and unadorned since my last trip to India.

I complain of this as I get dressed for the elephant excursion, which is silly. What is appropriate elephant-riding attire anyhow?

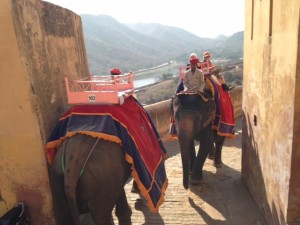

Turns out it’s not particularly comfortable riding an elephant. My husband and I sit in a boxy, pink palanquin with short bars that give us something to grip, but nothing to lean back against while the elephant clumps majestically from side to side. Our mahout sits astride the elephant right behind her head, which is privately how I’d pictured myself riding an elephant, once I’d come around to the idea. Her name is Rani, he tells us. Rani means queen.

“Is the elephant happy?” I ask the mahout. This is the kind of ludicrous question we’ve fallen into the habit of asking, just to give people the opportunity to tell us what we want to hear. Idiocy now clings to our clothes and hair like smoke; we can’t shake it. We’ve even reminded each other to stop asking questions with yes/no answers because the answer will always fall on the side of appeasement. Still, “How would you describe Rani’s general temperament?” seems unlikely to elicit any kind of intelligible response from the mahout. He has a nice smile and answers my question with much nodding of his head. “Rani happy! Rani very happy.” And to prove his point, he leans forward and puts it to the elephant: “Rani happy?”

In response, Rani’s trunk soars back towards us to nuzzle the mahout, who no doubt has elephant treats sequestered in his palm for just such a performance. Still, we’re delighted, and reassured that Rani is in good hands. We’ve been reading in the news about elephants — called tuskers in the local papers — who’ve gone berzerk at festivals, one dying in a marsh because no one could (or would) get her out of the mud. Another rampaged and killed two handlers who, the papers insinuated, may have been mistreating their tusker. We’re affronted by these stories, putting the blame squarely on the humans charged with the wellbeing of the animals and, indeed, the papers noted that the tuskers may have been forced to stand too long, in ceremonial garb, in the hot sun.

My mother-in-law loves the elephant ride; we all do. The only thing that feels off to me is that I never get to look Rani in the eye, to express my sheepish thanks in some way. I never get to lay my hand on her rough hide. We mount and dismount on high platforms and any interaction I might have had with Rani face to face once I’ve climbed off her is undermined by the now unsmiling mahout who, positioned squarely under the “Absolutely NO Tipping” sign, starts hissing at us angrily for a tip. The closest I get to even seeing Rani or getting any real sense of her is when I lean out the back of the palanquin and glimpse her vast rear-end, strewn with sparse grey hairs, and watch her languidly swinging tail.

We take photo after photo of Pat on her pachyderm, all of them slightly off kilter as we lurched to and fro. Days later Subir remembers to tell us the story he’d held back on earlier. It involves a tusker forced to do too many trips up to the fort who finally rebelled, scooping up one older lady tourist with his trunk and dashing her on the stones, then doing the same with her beige companion. “Both died,” Subir says sternly, glancing side to side under his hooded eyes. He’s not joking, although he’s clearly amused that he convinced us to ride the elephants before telling us this story. “Two French ladies,” he offered, as if this might help explain things. Now the Amber Palace tuskers are only allowed a limited number of trips up the hill and are off duty by 11 am. Hence, also, the high platforms for embarking and disembarking.

Later I scroll through Pat’s photos of us: she’s also taken dozens, off-angle, from her jolting seat on the elephant behind us. On the tiny viewer, I’m surprised and comforted to see my mum in her billowing travel uniform, lurching sideways in her perch beside my husband, smiling under the Rajasthani sun.

You’ve been visiting Jaipur. For more of this journey, check out Agra, Varanasi, and Delhi.